Sometimes it’s the choice you never imagined making that winds up changing everything.

Sometimes it’s the choice you never imagined making that winds up changing everything.

As a master’s student in medical imaging at the University of Surrey, Thirimachos Bourlai was preparing to enter the job market. He’d come to England after two years serving as an officer in the army in Greece, inspired by researchers who’d given his brother life-changing cancer care in Surrey. He assumed he’d move into a typical corporate career after he finished his degree. But faculty in the electrical and computer engineering program had a different plan in mind for him.

When Josef Kittler, founder and head of the Center for Vision, Speech and Signal Processing (CVSSP), summoned Bourlai to his office and offered him a spot in the PhD biometrics program, Bourlai had to admit that he didn’t know what biometrics was. Kittler, who went on to become Bourlai’s mentor, looked at him and asked, “Well, are you interested in learning?” Bourlai thought a moment before replying, “Sure.” That conversation marked the beginning of a journey he had never expected to take—and a decision that transformed his future.

Today, Bourlai is an associate professor in UGA’s School of Electrical and Computer Engineering and the founder and director of the Multispectral Imagery Lab (MILAB). A gifted researcher with adjunct appointments in the Institute for Cybersecurity and Privacy at UGA, as well as in ophthalmology, chemical engineering, electrical and computer engineering, and forensic science at West Virginia University, Bourlai applies machine learning and deep learning algorithms to decision making processes, helping technology learn to make the right choices for facial recognition, especially in less-than-optimal conditions.

When it’s nighttime or someone is outdoors, fluctuations in light and distance can make it hard for cameras and related technologies to identify potential threats. Bourlai’s team at MILAB designs and develops computer algorithms make better recognition decisions, in part by providing new data sets for machines to learn from. These databases, in combinations with the right algorithmic tools, aim to enhance the accuracy of mobile biometrics for multiple purposes, from national security to healthcare to facemask compliance in the era of COVID-19.

His work is generating significant interest due to its national and international impact. Bourlai recently completed a Department of Defense STTR Phase 2 project to create a publicly available database that advances facial recognition technology and algorithms at different distances. Conducted in collaboration with Mukh Technologies, Bourlai and his student team used visible and thermal camera technologies to collect imaging data on four hundred people. They focused on real-world conditions that can make it hard to detect and recognize human faces at a distance.

“My students did a fantastic job collecting and processing this data,” says Bourlai. “This process involves time consuming and painstaking tasks and they have been very professional. I am proud of them.”

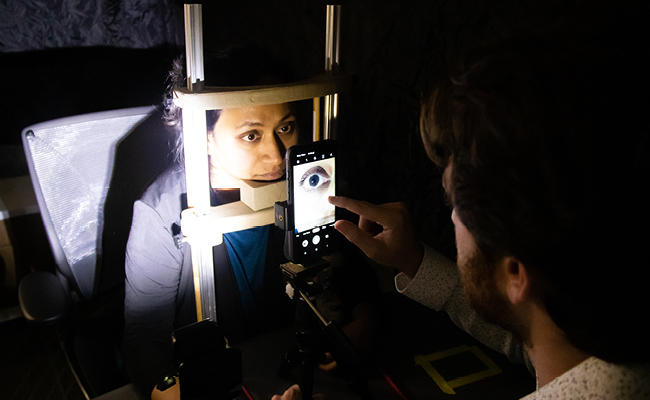

His current project is even more ambitious. Bourlai is collecting face and iris data from a planned 650 volunteers that can be used in different scenarios, such as developing and improving the efficiency of cellphone-based biometric algorithms.

“In many scenarios, there’s not enough data currently out there to work on challenging biometric tasks,” he says. “For example, eyes are dynamic, and they dilate. When this happens, it changes the structure of the iris, which can affect the performance of iris recognition algorithms.”

The study, which is actively recruiting volunteers, will utilize biometric and demographic data to build an image and video dataset for future applied research, training materials, competency testing, and more. Long term, this database—which will not be publicly available—aims to improve face and iris recognition technology.

At the same time, privacy concerns are paramount in Bourlai’s research — and across his entire field. As mobile biometrics makes its presence felt across everyday life, affecting everything from home security systems to a patient’s ability to text a photo of an odd-looking mole to her dermatologist, privacy-laden technologies are becoming ever more vital. The future lies in biometric related innovations that protect privacy and confidentiality even as they offer enhanced recognition solutions, says Bourlai. Ethical considerations play a key role here: he says researchers must prioritize identity protection, not simply identification.

It’s a fast-changing field, inherently competitive and interdisciplinary. But at the end of the day, for Bourlai the most important ingredient for successful research is the community behind the project. That means finding the right students, those with creativity, drive, and a determination to see something through. And although Bourlai’s resume attests to his experience helping machines learn to make the right choices, his greatest joy lies in helping students learn to make the right choices—for their careers, for those futures they might not yet be able to imagine.

Bourlai will never forget those faculty members who saw his potential back when he was a student.

“Sometimes you don’t know what you’re going to do,” he says. “You think one road will lead you to a better life, but then you might meet people who have more experience and who can see something else in you.”

Bourlai believes what matters most are the relationships one builds along the way—aiming to build connections with students and colleagues that will last. Building the next generation of technologies with diverse, dynamic, and well-bonded teams is the key to success.

Bourlai also believes in mentorship and supporting all students with good advice.

“If someone with good intentions and with experience in life and their field of expertise sees something in you, give them a chance,” he says, reflecting on what he tells his students at the start of each academic year. “If they see something in you, if they believe in you, maybe try taking that path. It might lead to an even better life than the one you thought was possible.”